A By-Name List (BNL) is a comprehensive list of every person in a community experiencing homelessness, updated in real time.

“Using information collected and shared with their consent, each person on the list has a file that includes their name, homeless history, health and housing needs. By maintaining a BNL, communities are able to track the ever-changing size and composition of their homeless population. They know current and detailed information on every homeless person in a given subpopulation.” (Built For Zero – Community Solutions – “What is a By Name List?”)

A BNL provides a baseline assessment that would enable the County to focus on what should be its primary goal: Reducing the actual number of people living outside.

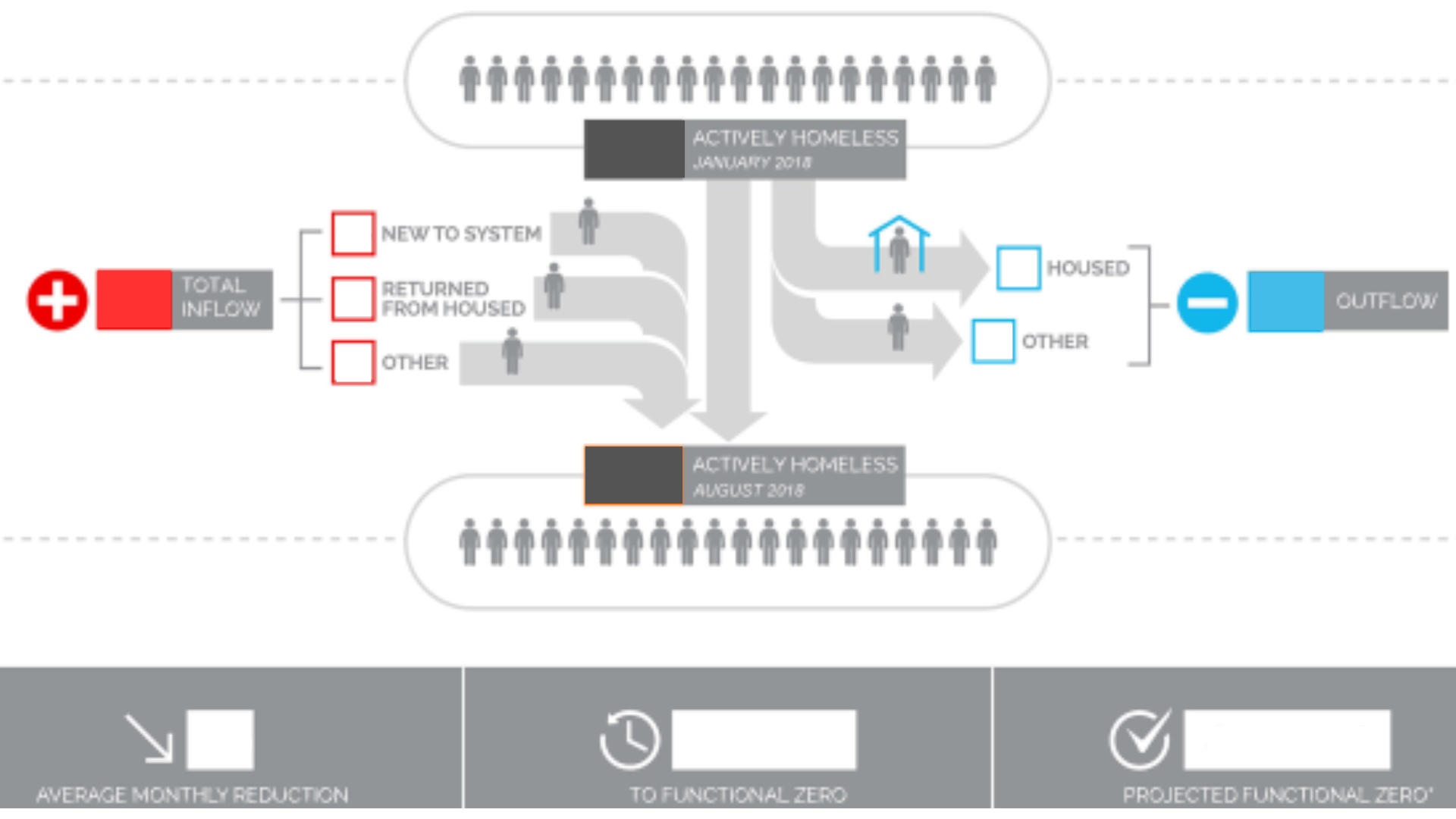

The actual number of people living outside reflects the entire homelessness to housing (H2H) continuum, including the number of people becoming homeless (inflow) and those leaving homelessness (outflow), as well as those living on the streets and in shelters. The number allows the County to use real information to drive change, assess progress, course-correct, and promote meaningful outcomes.

If the number of people living outside is increasing, the County is failing at preventing homelessness, transitioning people into treatment or other needed services, and/or housing people. If the number is decreasing, the County is succeeding in its efforts.

This approach, coupled with the focus on each person’s unique needs and barriers, can provide a roadmap to both optimize individual pathways to housing and guide collective investment.

Other counts, including the Point In Time Count (PITC) and the County’s version of the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS), are NOT BNLs.

The HUD-sponsored Point In Time Count (PITC) relies on volunteers and service providers who are deployed across the county on a couple of days each year to pose a set of standardized questions to people they encounter who appear unsheltered. There is no effort to seek people out who are off the beaten path, and people who are sleeping, having a behavioral health crisis, or otherwise are not able to engage do not get counted. Meanwhile, these are the people most in need of identification.

There is no way to track people to get them what they need. The questions are typically awkward, poorly phrased and do not get at vital information that will help people transition out of homelessness. If there are fewer volunteers, the numbers will be lower. The PITC is a fundamentally flawed process that wastes valuable time and resources that would be better spent on a BNL.

The County has needed to consolidate and restructure its BNL, HMIS, and PITC processes for years. It has not done so. The HMIS process is discussed in more detail below.

A BNL uses a common-sense approach to achieve not only individual progress by getting people stably housed, but global progress by optimizing investment.

- Using information to help individuals: Using individual information, intensive care teams can establish relationships, follow people through the H2H continuum, help with transitions, get people what they actually need, problem-solve in real time, and facilitate their flow along a pathway to housing.

- Using information to guide investment: Aggregated information can identify what’s collectively needed to get people off the streets into the shelter/housing that meets their needs. It can inform an effective evidence-based plan to reduce the number of people living outside. This data is essential to guide responsible investment by the City and County in a Homelessness-to-Housing continuum.

Despite years of spending, Multnomah County still does not have a BNL.

Having brought the concept of a BNL to the County four years ago with City Commissioner Dan Ryan, I directly observed the County’s failure to build one and witnessed the reasons why. There was initially overt antipathy of County leadership toward implementing a BNL. Then, there was masked antipathy as the County began to implement the program, but delayed and did not invest. Then, there was a misunderstanding, further delay, and posting of information that was inaccurate.

Over the past year or two, the desire to create a BNL seemed more authentic than it had in the past. However, there never seemed to be an authentic understanding of what BNL actually was, or its power as a tool to effect change.

Without an accurate and complete BNL, the County does not know how many people live unsheltered on its streets, what they need, or how to best invest resources to achieve the most good. Most importantly, the County will not be able to assess programs or track progress in terms of impact on real people and the community.

The County calls its Homelessness Management Information System (HMIS) a BNL. It isn’t.

Summary of HMIS:

HMIS is a federal database containing information about people who are homeless. Entry of certain information into this system is required by jurisdictions receiving HUD money to address homelessness. The County took over HMIS from the City after a protracted and opaque process.

The local HMIS was archaic even when it was first adopted over 20 years ago. Over the past two years, the County has talked about updating its HMIS, even though it hasn’t done so yet. It has spent money on HMIS, but because investments were made through different departments and with different funding streams, it is virtually impossible to follow the money.

At the time I left the board, it was not possible to identify exactly how much had been spent on “updating” HMIS, what departments were involved, how the County engaged with its partners around use of HMIS data, where the County was in terms of implementation, what information was being collected by whom, or how effective its investments had been. The board has the power to demand this crucial information during the County budget process and beyond.

Even if the HMIS does what the County says it’s doing, it is still not a BNL.

Although an HMIS can potentially constitute a BNL, the County’s HMIS doesn’t.

The County’s HMIS offers a passive, retrospective, grossly incomplete, and often inaccurate list of people who are treated as numbers in order to comply with HUD regulations. It is not used to guide investment in a functional H2H continuum.

In stark contrast, a BNL offers an intentional approach to identify all people living outside so as to understand their needs and get them stably housed. It is used to proactively guide collective investment in a functioning H2H system and treats the people it identifies as human beings.

Here is a specific breakdown of the fundamental differences between the County’s HMIS and a BNL:

- Purpose: Compliance vs. People.

HMIS is a required compliance tool for HUD, wherein people are treated as numbers. A BNL provides information about real people in order to get them what they need to get and stay housed, and make sure this gets done.

- Engagement: Retrospective and passive vs. real-time and proactive.

County HMIS contains information passively obtained through different providers that is retrospective and static. A BNL engages teams to proactively and intentionally engage with people in a structured way to identify their needs and barriers in order to directly address them.

- Accuracy: Limited vs. Full

County HMIS includes names of people who have died, variations on multiple names counted as separate individuals, and people who have moved away, gotten housed, gone to jail, or gone to the hospital. Although they are working to deduplicate names and scrub data, the problems are unavoidable given the County’s approach. A BNL identifies and actually follows people to know what is happening with them. Their information is updated in real time.

- Completeness: Limited vs. Full

County HMIS only contains information submitted by a subset of County service providers for people already engaged in County services. Numbers can be off by hundreds to thousands. A BNL contains information about everyone living outside, because teams intentionally and directly reach out to people in a planful way to establish and build relationships and regularly update information.

- Collective impact: None vs. Foundational

County HMIS is not used to identify how collective investments can be optimized to provide the most good for the most people. A BNL considers driving effective investment to be a core purpose.

The County’s false reliance on the HMIS as a BNL has resulted in false promises of false deliverables, leading to false claims of success in its supposed Homeless Response Action Plan (HRAP).

As a commissioner, I openly conveyed my concerns about the HRAP. These included: (1) Creation of a huge new bureaucracy on top of an already dysfunctional one with no clear chain of command or purpose; (2) Added cost and confusion with no clear benefit; (3) Governance that was not independent of politics and lacked expertise; and (4) Metrics and deliverables that were severely flawed and would not lead to a decrease in homelessness. It flew under the radar and was approved with virtually no attention by County commissioners or the media.

I prepared a memo (detailed) and summary (less detailed) that explained my concerns to the Chair, the former Mayor, the former city council, and the former county board at the time the HRAP was being voted on. Many of these concerns have borne out.

One example shows how the County’s treatment of its HMIS as a BNL leads to false promises, misleading deliverables, and potentially absurd results:

- The promise: The HRAP promised to decrease the number of people living unsheltered by 50% by the end of 2025, according to the County’s “by name list”.

- The reality: The HRAP agreed to take the number of people listed in its HMIS as of January 25, 2024 (5400), divide that number by 2 (2700), and promised to shelter or house that number of people by the end of 2025. It did not promise to do anything about the actual people on the HMIS list, or to house half the number of people actually living unsheltered as of January 25, 2024.

- The implication: Erroneously using the HMIS as a BNL allowed the County to start with an inaccurate baseline, count anyone they could find living on the street over the next two years, and claim success if they moved them somewhere, even transiently.

- The absurdity: JOHS could claim success even if it did not help a single person on its original list; if the net number of people living unsheltered actually increased; or if people who moved into shelter or housing ended up back on the streets the next day.

If this were a BNL, People on the list would be individually followed, the list would be updated as people came and left, and the County would ensure that the number of actual people living unsheltered was going down because people were actually being served.

The same problems exist with all of the HRAP’s deliverables, such as the promise to eliminate discharges from hospitals to homelessness (a ludicrous promise, made even more so by the fact that the County did not engage with hospital administration or understand the extent of discharges to homelessness before making the promise).

CONCLUSION – Multnomah County needs to urgently complete a real BNL.

Last year, I proposed a budget amendment that would have urgently established a meaningful BNL by the end of the calendar year. It invested in an incident command-style structure to deploy dedicated teams in a coordinated way to proactively and intentionally identify people living outside and create a consistent list. The budget amendment was voted down by the board.

The investment itself was relatively small, but the return on investment in terms of finally understanding who the County is serving and what’s needed to serve them would have been invaluable. A BNL would not only answer basic questions about the County’s homeless population and homeless services system, but also allow the County to invest effectively in what’s needed to actually reduce homelessness, assess the effectiveness of programs, and track progress in achieving one clear goal: Reducing the actual number of people living outside.

As the number of people dying outside has skyrocketed, and massive budget shortfalls loom, it is even more urgent that the County invest its limited resources in a coordinated, data-driven, measurable, and cohesive way to save lives and help the most people.